When you think of Southern California, what plants come to mind? Perhaps it’s palm trees lining the streets of Los Angeles, citrus orchards cascading across Orange County, or eucalyptus groves offering a fragrant canopy on college campuses. However, these trees are not native to the area and sometimes do more harm than good, representing a form of botanical conquest that is anything but natural.

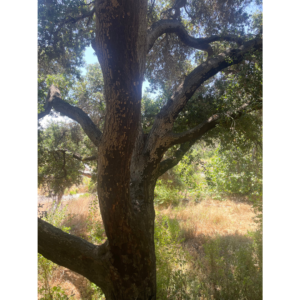

It’s the oaks that are the cornerstone of life in this region. On a walk in Pasadena last spring, I smiled at the sight of a Coast Live Oak growing horizontally out of the side of a towering Mexican Fan Palm, probably grafted there by an industrious Acorn Woodpecker. With the beginning of a new year, I resolve to be more like the woodpecker–a cheerful and hardworking cultivator of oaks.

Since reading Doug Tallamy’s book, Nature’s Best Hope with A Rocha USA’s Love Your Place book club, I’ve been reinvigorated to do my part in grassroots conservation. Calling attention to the massive decline in global wildlife populations, Tallamy offers a fairly simple solution: native plants. These plants have co-evolved with animals, fungi, and microbes to form a complex web of relationships. They are the best-suited plants for their climate and soil type, meaning they don’t need supplemental water or fertilization, and they provide the maximum number of benefits to an ecosystem. Plus, they are easy to grow by anyone!

Tallamy proposes that if each American landowner were to convert half of their lawns to productive native plant communities, we would restore functioning ecosystems to over twenty million acres of what is currently “ecological wasteland”. Through this joint effort, we would create the country’s largest national park system, what he calls the “Homegrown National Park.” (pg 62)

As I fall deeper in love with California’s native plants, I find myself amazed yet overwhelmed by the biodiversity of this place. California has 6500 native plants (more than any other state in the U.S.), a third of which are found nowhere else on Earth. As a new but eager gardener, I’m unable to cultivate even a fraction of these species. Tallamy’s solution to maximize biodiversity with limited space, knowledge, and time is to focus on keystone species. These plants have a “disproportionately large effect on the abundance and diversity of other species in an ecosystem.” (pg 139) When keystone species are absent, the food web all but falls apart.

Thus, we return to the mighty oak. With hundreds of species of oaks living around the world, there are likely multiple supporting your local ecosystem. I’ve begun spending more time with the oaks, joining the long list of creatures that these great trees support: over three hundred vertebrate species and almost five thousand insect species. I’ve seen Western Fence lizards doing comical push-ups at the base of the tree; California Ground Squirrels–which are, themselves, a keystone species–caching their seeds; California Scrub Jays hopping around in the sunlight; and California Sister butterflies announcing the beginning of spring.

In her book Secrets of the Oak Woodlands, Kate Marianchild documents several of these endearing creatures. She also asserts that Indigenous Californians are a keystone species: their interactions with the natural landscape were and are essential to a thriving ecosystem. An Indigenous educator, Nicholas Hummingbird, speaks of a time before colonization when one could walk from the San Gabriel mountains (known by the Tongva as Yoát, meaning “snow”) to the beaches of Malibu (meaning “the surf sounds loudly” in Chumash) without ever leaving the shade of an oak. This knowledge shows a way of being where the human presence in an ecosystem not only refrains from harm but contributes to flourishing webs of life.

What we have now is far from this ideal. In the face of a global biodiversity crisis and accelerating climate change, there are statistics that we can’t unlearn, changing landscapes that we can’t unsee, the burden of a groaning creation that we can’t shrug off. Given all this, to be a part of the life of an oak brings me hope. While volunteering at a native plant nursery, I carefully transfer Coast Live Oak seedlings into larger pots, observing how their tap roots already reach down, eager to be in the ground. It’s an opportunity to pray for the creatures who will reside among these trees and work for their well-being.

In the spring of 2023, I planted an oak tree for the first time on the side of my church; it’s surrounded by other native plants and already enjoyed by a myriad of insects, birds, and people. Especially for those of us who don’t own land, churches are a great space to care for creation by planting native plants (stay tuned for more resources from A Rocha coming soon!). Planting an oak is possibly the most significant action I can take to combat climate change and biodiversity loss. And it is significant! Many massive oak species can sequester tons of carbon in their wood and roots, pumping tons more into the soil. Alongside supporting animals and insects, an individual oak will associate with over a hundred species of fungi throughout its life and will help prevent erosion and encourage rainwater to infiltrate the soil (learn more about the importance of fungi for biodiversity and interconnected ecosystems here).

Six years ago, the Santa Monica Mountains were devastated by an enormous wildfire. Each year during fire season, I feel afraid imagining what may be destroyed or lost: with love for a place also comes the possibility of loss. This year I hope to make hiking in this area a regular practice. I follow the trail where the Malibu and Las Virgenes creeks meet in a prehistoric-looking landscape, wandering beneath the canopy of oaks charred by wildfire. Each creature and plant I notice in this woodland is a message of hope for a restored ecosystem.

How humbling it is, to participate in the life of these plants. Not one of us can solve the conservation challenges we face, but each of us can have a profound impact: “It is your efforts as an individual that will determine whether we succeed or fail and whether we live in a world thriving with life or in one in which little stirs.” (Nature’s Best Hope, pg 23)

Anyone, anywhere, can contribute to the homegrown national park and the global effort to restore 30% of Earth’s lands, oceans, coastal areas, and inland waters by 2030. For resources on planting native native plants in your home, church, school, or local park, use the National Wildlife Federation’s Native Plant Finder. To join an encouraging and helpful community along the way, become a member of our Love Your Place program, and be sure to share your progress!

Oaks are indeed amazing! Good work, and great article!

I’ve always loved the mighty oak. Very interesting article. Makes you think. The pictures are beautiful too.