Sylvie Vanhoozer’s The Art of Living in Season reminds me of a French camellia: petals within petals, each layer enfolded in the next. Throughout the book, Vanhoozer depicts her childhood in the southern French town of Provence, then enfolds it in her cultural inheritance of the santons (the “little saints” of Provençal manger scenes), enfolds that in the cycle of the seasons, and enfolds that in the cycle of the church calendar. Together, they form a single blossom of culture, ecology, and spirit.

As she reflects on these linked themes, Vanhoozer encourages her audience, as “saints on an everyday pilgrimage,” to “relearn how to walk” (Vanhoozer 8). She invites us to slow down and pay attention. To take time to contemplate, on one hand, “the seasons of the church that teach us about Christ’s life and ministry,” and on the other hand, “the seasons of nature that reveal the goodness of our Creator” (7).

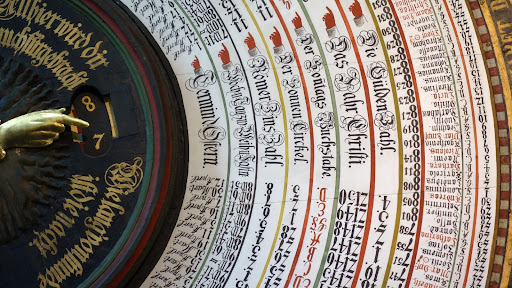

Cycles of church and nature: the book explores both in tandem, starting with early winter and Advent, then circling to late spring and Pentecost, before transitioning to Ordinary Time, to which half the book is dedicated. Though you can read the book straight through in a couple of weeks, you can also read it as a year-round devotional, timing each chapter to overlap with your current point in the church calendar.

Vanhoozer’s writing operates on two levels: church tradition and creative parable. She engages with the traditional meaning of each church season – such as Epiphany’s celebration of Christ’s revelation to all peoples, or Lent’s emphasis on fasting and introspection – then breathes fresh life into these themes with illustrations drawn from the santons and plant life of Provence. Jesus, of course, did something very similar when he told stories of farmers and mustard seeds.

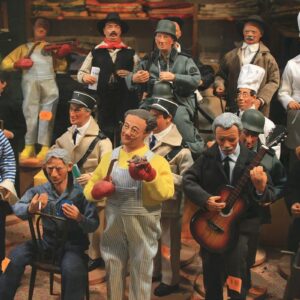

The santons are little clay figures that populate the Provençal nativity scenes, and they represent an array of local callings, from the more Advent-ish shepherds to people like farmers, fishmongers, chefs, flower sellers, knife grinders, elders, and children, all bringing their unique offering to the baby Jesus in his cradle. These tiny French saints challenge us to consider how we can integrate our unique cultural realities into the Gospel story, and the variety of vocations among them reminds us that Jesus’ presence flows into every nook and cranny of our lives, even those we might call mundane. Vanhoozer writes, “Jesus came not to abolish but to sanctify everyday life” (171).

Aside from the cultural parables of the santons, the book is full of ecological parables, too. In her poetic, playful tone, Vanhoozer describes the holly that Christmas hymns compare to Jesus’ blood, the buried hyacinth bulbs whose life remains aglow during winter-bound Candlemas, and the tomato and basil of Provençal gardens, which complement each other’s health in the soil and their flavors on the table, reminding us of the blessings of companionship. It’s as though the plants are pilgrims, too, joining the santons on their journey through the church calendar.

In considering this book’s significance for creation care, a key term is patrimoine. Though the word can refer to an inherited family estate, Vanhoozer explains that it encompasses all that a community “cultivates and passes down from one generation to the next, a kind of cultural DNA.” Ultimately, “the root of any patrimoine is its particular place on earth” (122-3). The uniqueness of a culture, in other words, stems from the unique crops, animals, resources, and landscapes that surround it. In the age of globalization, this dependence hasn’t weakened, but expanded, as cultures now draw from ecosystems around the world.

Vanhoozer insists that, when we consider passing down our cultural inheritance – our patrimoine – to the next generation, we can’t neglect ecology. Just as nurturing the soil will nurture the trees that grow from it, so nourishing our ecosystems will nourish our local cultures. This is yet another point where the needs of creation and those of humanity intertwine: if we can find ways of cultivating a sustainable ecosystem, then we might establish a sustainable culture as well, enduring from generation to generation.

Creation care itself is a kind of patrimoine, and it stretches right back to the book of Genesis, when “God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to work it and keep it” (Gen. 2:15). This is, as Vanhoozer puts it, “the world’s oldest vocation: the charge to work and keep the land, to put down roots in a particular place and flourish” (122). Such an inheritance is as joyful as it is ancient, and through her writing, Vanhoozer has taken her own role in preserving that legacy for years to come.

Learn more about santons, plant life, and the church calendar at theartoflivinginseason.com, or buy the book yourself at a bookstore of your choice!

Add a Comment