by Hannah Hubin

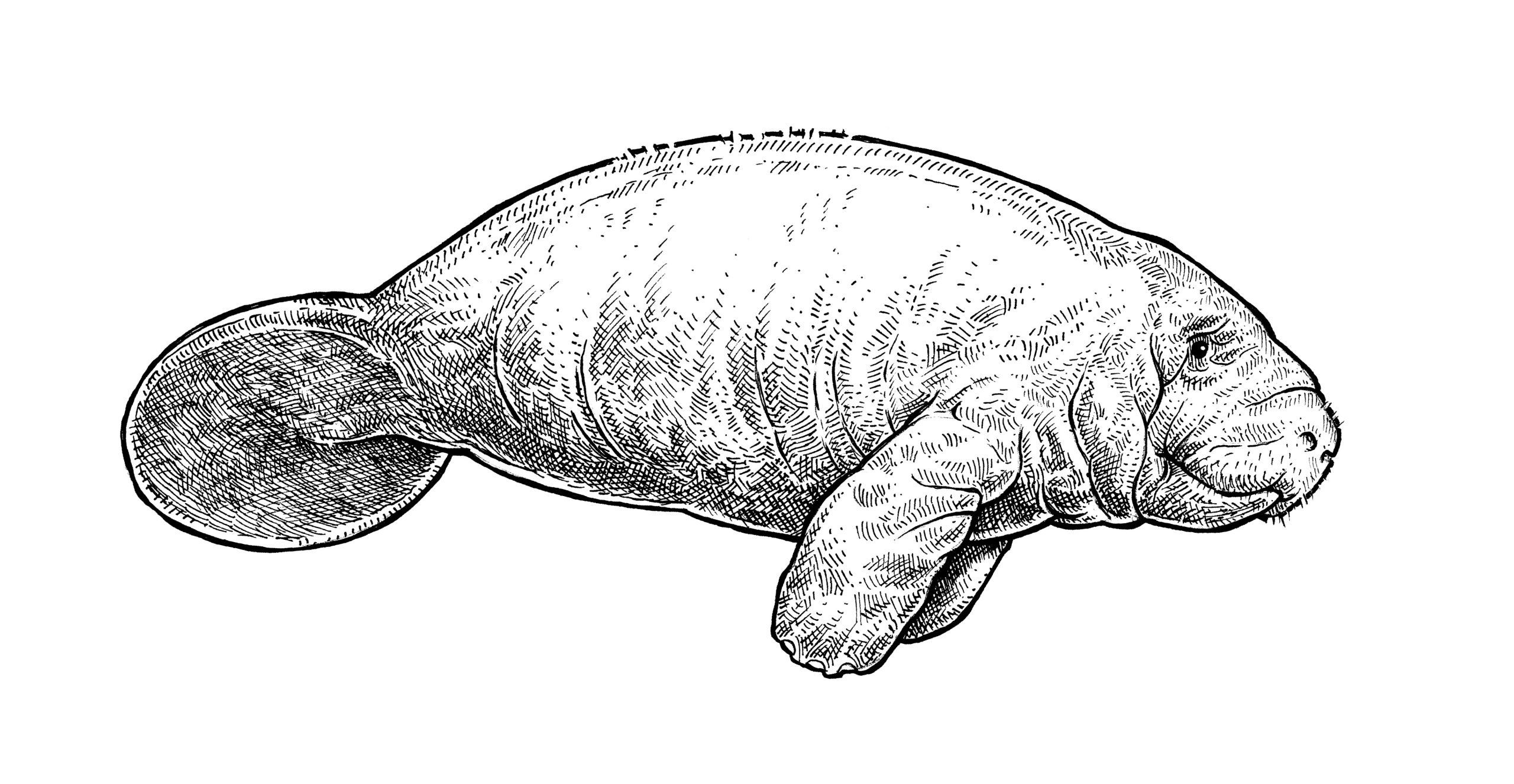

All images are by Matthew L. Clark, used with permission from Square Halo. You can see these illustrations yourself at an exhibition at the Square Halo Gallery in Lancaster, PA, from June to August 2025! Learn more here: Square Halo Gallery

I have long noticed that my favorite writers are often naturalists, farmers, “lay scientists.”

Of course, Annie Dillard and Wendell Berry and Mary Oliver come to mind immediately; they probably started this pattern for me. Then I’ve had the great joy of reading back through children’s books again and finding that the agrarian descriptions in Farmer Boy are far more captivating to me than any of the characters, and the survival instincts of little Sam Gribley of My Side of the Mountain kept me wanting to read another chapter, even when my 5th graders weren’t convinced.

Did you know that H.A. Rey, who with his wife Margret created the Curious George series, drew and published constellation diagrams still used in astronomy guides today? Lewis Carroll wrote an array of textbooks on mathematics, geometry, and logic – the same logic he turned upside-down in Wonderland.

These connections shouldn’t be so astonishing. J.R.R. Tolkien’s whole idea of sub-creation – that “we make still by the law in which we’re made” – should be enough to remind us that all great creativity has its start in the great creation.1 We’d be hard-pressed to find any writer, poet, or artist who hasn’t created out of his or her own utter fascination with some piece of the natural world.

Trout Lily (Erythronium americanum) and Southern Toad (Anaxyrus terrestris).

Why then do we, lovers of literature and art, often spend so little time in nature? We tuck ourselves away in coffee shops and bistros, turn our Bluetooth earbuds to “noise canceling on,” open the faux blank page of a Google Doc, and get to work – in exactly the same manner in which I’m writing this. It’s low-hanging fruit, I know, and technology isn’t the problem. But the posture of our hearts that leads us to believe this sort of afternoon has more to do with creativity than a walk in creation – well, that’s a little more concerning in the life of the artist.

And what about as believers? As someone who believes the most important narrative is one that begins in a garden with two central trees and four rivers and ends in a city with a great tree on either side of a river, I’m ashamed to say I know very little about trees or rivers.

It felt almost wrong to read Matthew Dickerson and Matthew L. Clark’s book Birds in the Sky, Fish in the Sea inside on my couch or in a coffee shop. I read it over the course of three days, sitting out on my deck in the first of the Alabama spring sun.

The “thesis” of the book, if you will, is straightforward enough, and because paraphrasing poets is dangerous territory indeed, I won’t try. Through this book, Dickerson suggests “that attentiveness to creation is a meaningful spiritual act (or spiritual discipline) with several important benefits or goals; that God invites us to such attentiveness; and that to be attentive to creation as well as to the Creator – or, we may say, to be attentive to creation as a way of being attentive to the Creator – is an act of worship.”2

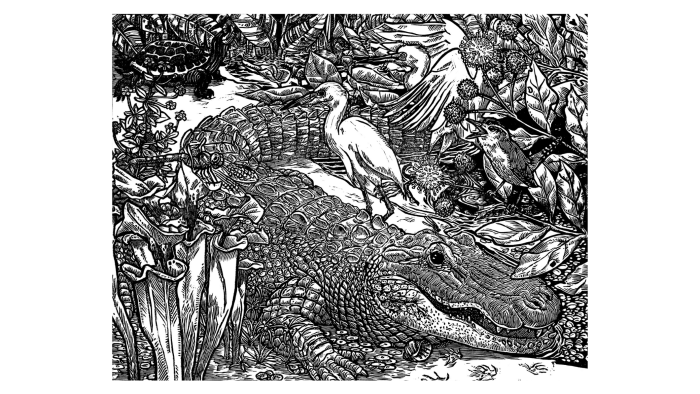

American Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) and other species.

The book has five chapters, each with a short essay followed by narrative non-fiction prose and poetry. Dickerson writes of various climates and preserves he’s visited and the acres of woodlands he himself tends, observing both plant life and wildlife. But the words only tell half the story.

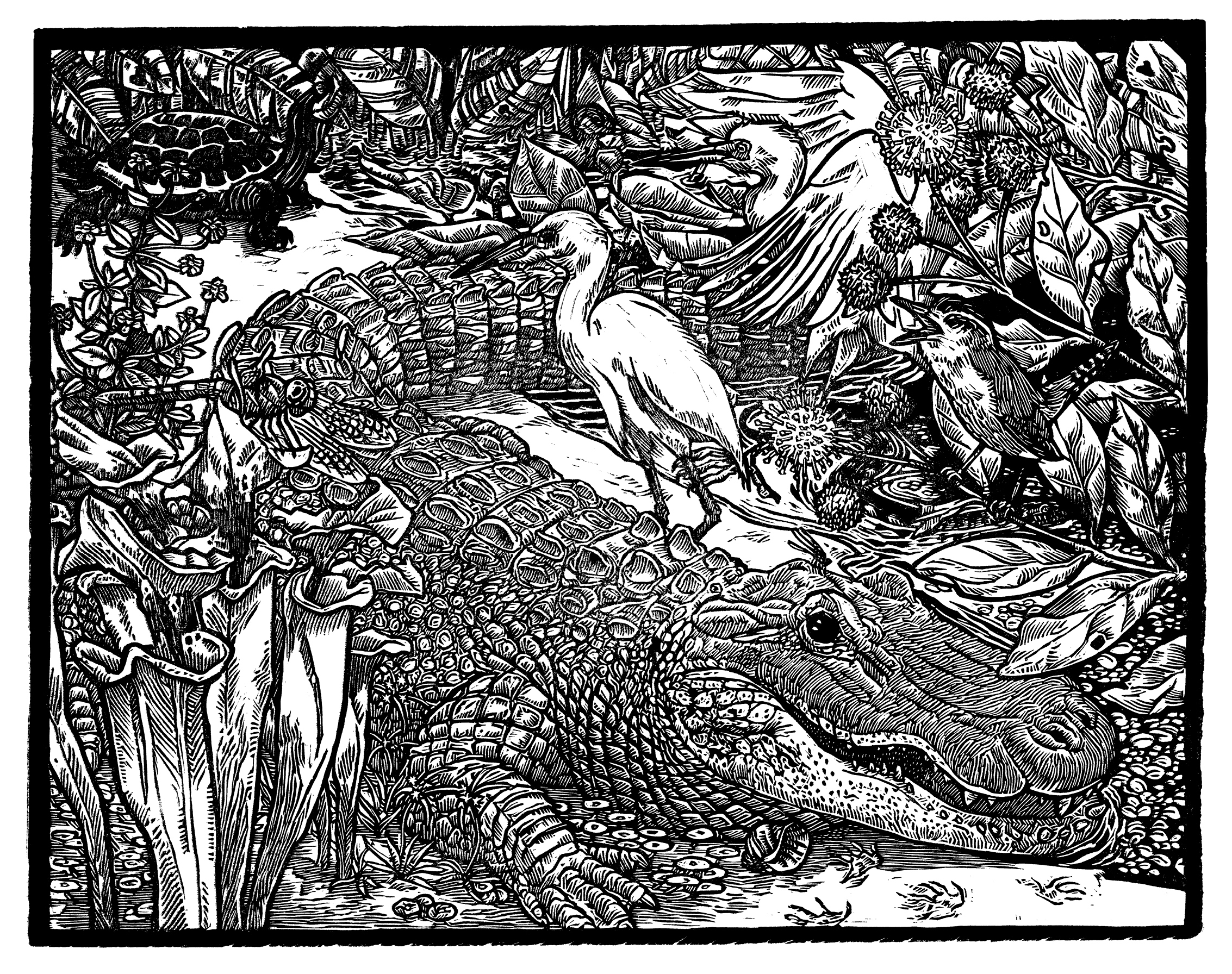

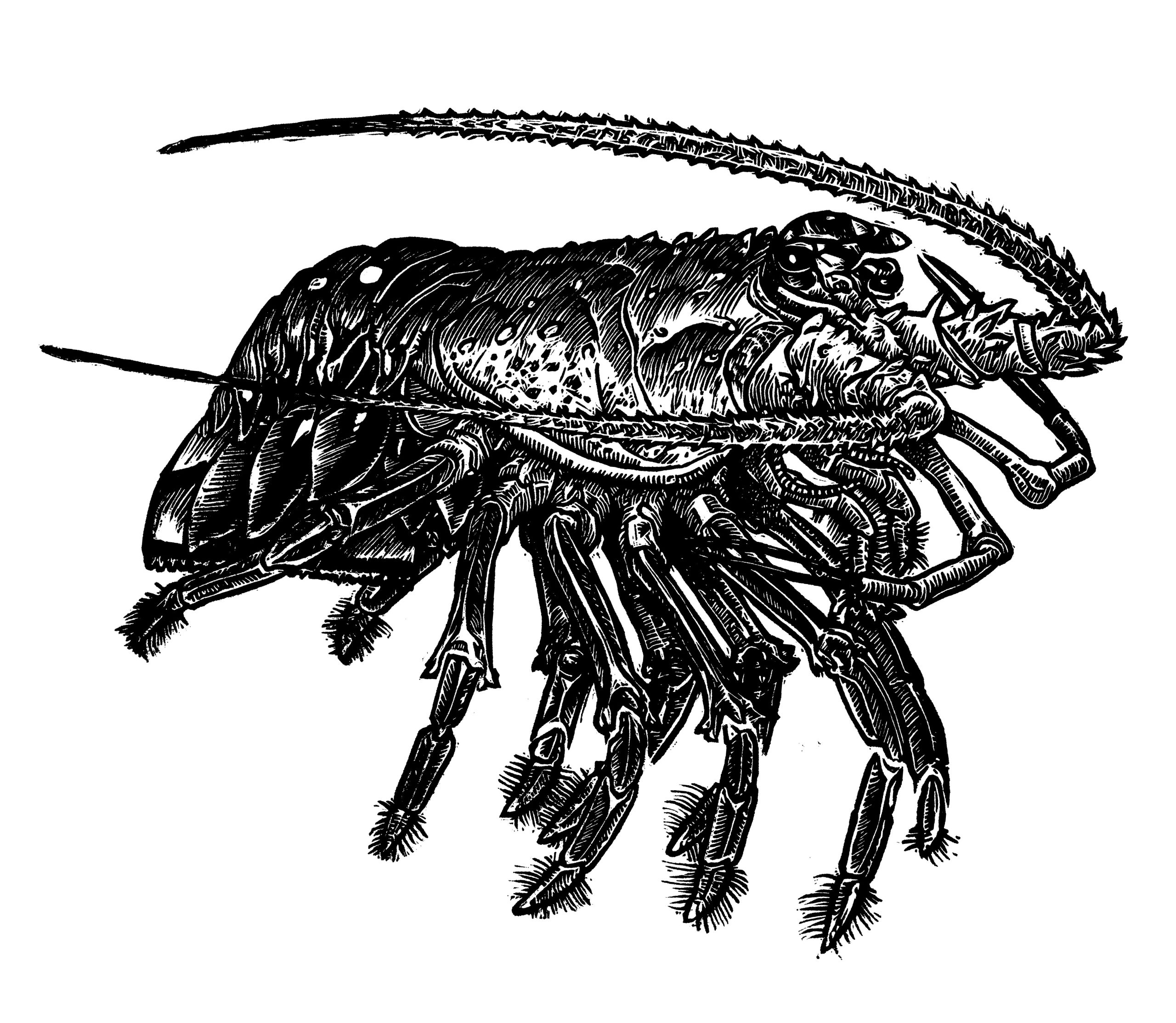

Clark’s pen and ink drawings, copper etchings, and linocuts pattern every single page: freshwater creatures, land animals, insects, flowers, and yes, birds of the sky and fish of the sea. It’s a small book, roughly 150 pages, almost pocket-sized, itself resembling a nature guide of sorts. In fact, each of Matthew Clark’s illustrations can be found in an identification guide in the back, with the common name and scientific name of each plant and creature.

As our “guide,” the book is first and foremost invitational. Attentiveness, wonder, and delight are the key words here. While the first two chapters focus on observation and experience – introducing the idea of attentiveness to creation as spiritual discipline – the third chapter focuses on the vital place nature serves in our vitality, “restoring the soul.” Chapter Four’s title is “Attentiveness and Christian Vocation: The Holy Work of Creation Care,” and Chapter 5 discusses “Lamenting with Creation as a Holy Vocation,” explaining our call to play a part in the renewal of the earth. No, there is no petition in the back to sign, and this is no campaign to save any one thing in particular – except perhaps our souls. This book is first and foremost a matter of affection.

What might be even more impressive is that the project isn’t some attempt to exploit creation for our own metaphorical ends. Dickerson and Clark masterfully avoid the temptation to “use” rather than “receive” nature (as Lewis talks of reading literature in An Experiment in Criticism). Dickerson reminds us that, in the “birds of the air” and “lilies of the field” illustrations from the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew 6, Christ shapes an analogy only after bidding his listeners to look and see.

American Kestrel (Falco sparverius).

As Dickerson explains, “I think we make a mistake if we jump too quickly to this spiritual lesson without taking time to obey the opening commands: pay attention to the birds and the flowers.”3 Missing this first part is “a bit like trying to know God without taking the time to be still” (Psalm 46:10),4 or skipping to the end of a movie, or reading just the last chapter, or coming late to church to avoid the music and leaving before the passing of the peace and the Eucharist. It’s trying to know and love a person without caring about the things he or she wants to share with you.

Dickerson and Clark take a page from their own book in their book. Yes, there are plenty of metaphors and analogies, even lessons, for the spiritual life in these pages. But there are also just descriptions – of salmon and rainbow trout, of manatees and herons, of sea otters and birch trees; and images, so many images – Carolina Chickadee and King Mackerel and Florida Bark Scorpion. I know their names, and what they look like, because of this book.

I never found myself “bracing myself” for the moral of the story as I read. I think this is what I mean when I call the book invitational: that I mostly just found myself thinking, I would like to see that. And, as I went on, I would like to become the sort of person who notices that.

Caribbean Spiny Lobster (Panulirus argus).

I’ve been listening to C.S. Lewis’s Out of the Silent Planet during my walks this week. I have little patience for anything remotely adjacent to science fiction (a fault on my part, I know) and even less patience for audiobooks in general, so the whole venture is rather tenuous. But Lewis has kept me drawn in thus far with some fantastic descriptions. One is his depiction of Ransom’s first exit from the spacecraft onto the unknown planet of Malacandra: “He saw nothing but colours – colours that refused to form themselves into things. Moreover, he knew nothing yet well enough to see it: you cannot see things till you know roughly what they are.”5

Without people like Matthew Dickerson and Matthew L. Clark, without books like this, I feel a bit like Ransom. How can I hope to see the life and creatures of this world – this planet – if I don’t know what they are? Whenever I’m tutoring Greek or Latin or Hebrew, I often explain to my students that one of the reasons I care so much about learning ancient languages is that they provide us with new words – words that unlock hidden realities, for how can we think about something if we don’t have words for it?

Reading Birds in the Sky, Fish in the Sea feels a bit like learning another language, which means I must admit that the life within my own backyard often feels “foreign” to me – another vocabulary, another planet. Part nature guide, part devotional, part biblical theology, part sacramental theology, this book is a kick in the pants for those of us who have the tendency to think that nature is not our “thing.” Dickerson and Clark gently acquaint us with our own world and remind us that we are all called to know and care for a beautiful and groaning creation. This book is a call to move toward Eden as we live now in the Kingdom of God.

West Indian Manatee (Trichechus manatus).

You’ve likely heard Annie Dillard’s line, “How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.”6 Every day that I spend deciding that what goes on “out there” in creation cannot matter as much or at all for what goes on “in here,” I am making a decision for my life. What if I come to find I never really lived in this world at all? That I might well have been on Malacandra for all I know? That I never did that primordial, distinctly human task of keeping and tending the garden?

I am grateful for this invitation – to come back home, today, to my own world and to know it as my own for the first time, to know better the God who made it and me and loves both, and to be part of this task of making it new. I am also now hoping to meet a manatee – very soon.

- Tolkien, J.R.R. “On Fairy-stories,” Oxford University Press, 1947.

- Dickerson, Matthew. Birds in the Sky, Fish in the Sea, Page 15, 2025.

- —. Page 21.

- —. Page 22.

- Lewis, C.S. Out of the Silent Planet, Chapter 8, 1943.

- Dillard, Annie. The Writing Life, Chapter 2, 1989.

Hannah Hubin is a writer, poet, and lyricist. Her projects include All the Wrecked Light: A Lyrical Exposition of Psalm 90 and the online visual poetry project “Brown Brink Eastward.” She writes for the Rabbit Room and Every Moment Holy, teaches humanities, writing, and Latin, and is currently pursuing postgraduate studies focused on Hebrew poetry.

AllTheWreckedLight.com

Add a Comment